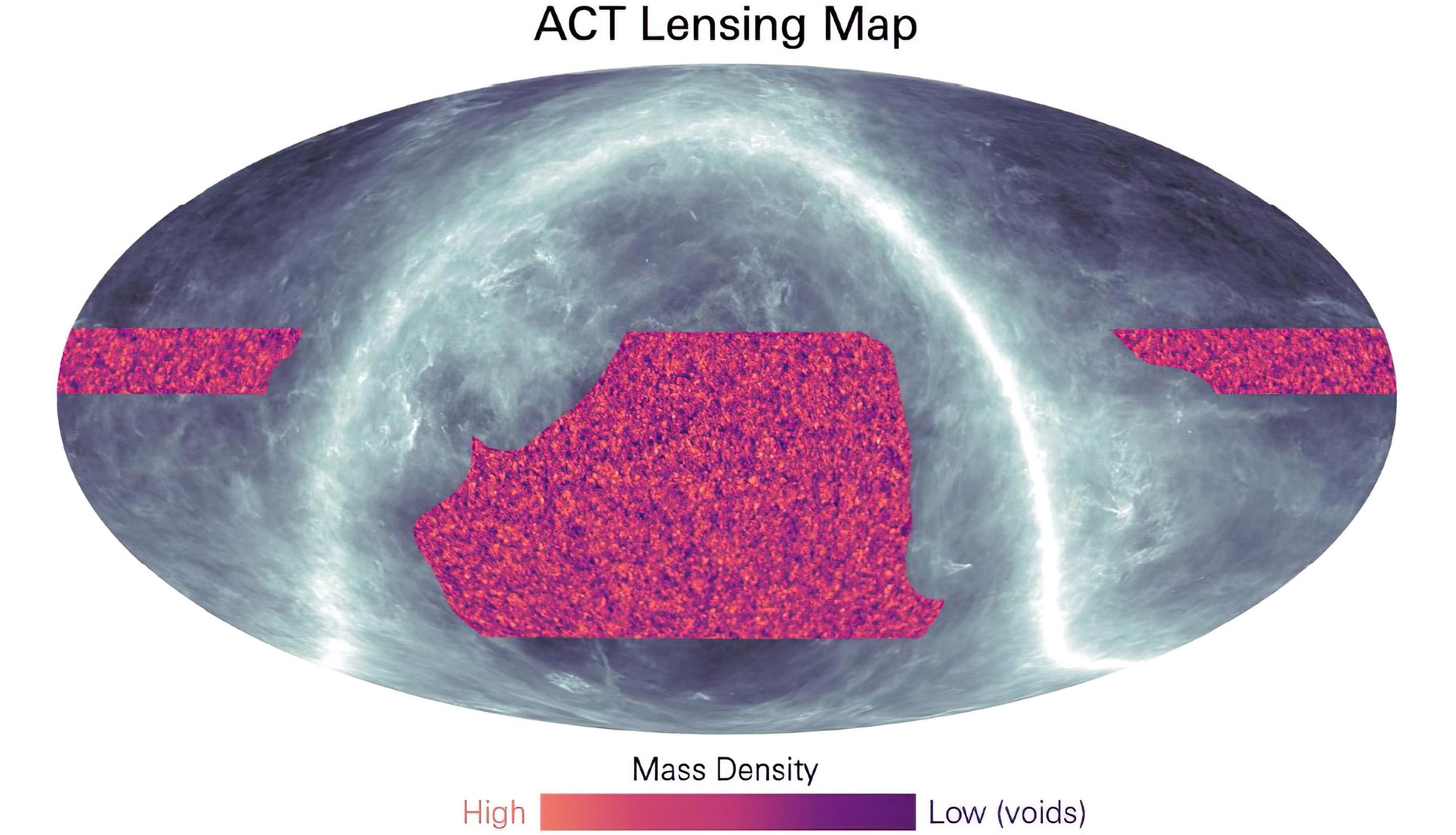

Naukowcy wykorzystali Teleskop Kosmologiczny Atacama do stworzenia nowej mapy ciemnej materii. Pomarańczowe regiony pokazują, gdzie jest więcej masy; Magenta, gdzie jest mniej lub nie ma go wcale. Typowe cechy rozciągają się na setki milionów lat świetlnych. Białawy pas pokazujący, gdzie światło jest przesłonięte przez pył w naszej Drodze Mlecznej, zmierzony przez satelitę Planck, zapewnia głębszy widok. Nowa mapa wykorzystuje głównie światło z kosmicznego mikrofalowego tła (CMB) jako światło tła do zobrazowania wszystkiego między nami a Wielkim Wybuchem. „To trochę jak cieniowanie, ale zamiast tylko czerni w sylwetce, masz teksturę i grudki ciemnej materii, jakby światło przepływało przez zasłonę z tkaniny z mnóstwem sęków i wypukłości” – powiedziała Susan Staggs. Henry D. Wolfe Smith Profesor fizyki na Uniwersytecie Princeton. „Słynny niebiesko-żółty obraz CMB jest migawką tego, jak wyglądał Wszechświat w jednej epoce, około 13 miliardów lat temu, a teraz dostarcza nam informacji o wszystkich epokach od tego czasu”. Źródło: Współpraca ACT

Badania przeprowadzone we współpracy z Atacama Cosmology Telescope zakończyły się wielkim przełomem w zrozumieniu ewolucji wszechświata.

Od tysięcy lat ludzkość fascynowały tajemnice wszechświata.

W przeciwieństwie do starożytnych filozofów, którzy wyobrażali sobie początki wszechświata, współcześni kosmolodzy używają narzędzi ilościowych, aby uzyskać wgląd w ewolucję i strukturę wszechświata. Współczesna kosmologia sięga początków XX wieku, wraz z rozwojem ogólnej teorii względności Alberta Einsteina.

Teraz naukowcy z Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) Collaboration przesłali zestaw dokumentów do the[{” attribute=””>Astrophysical Journal featuring a groundbreaking new map of dark matter distributed across a quarter of the sky, extending deep into the cosmos, that confirms Einstein’s theory of how massive structures grow and bend light over the 14-billion-year life span of the universe.

The new map uses light from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) essentially as a backlight to silhouette all the matter between us and the Big Bang.

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Northern Chile, supported by the National Science Foundation, operated from 2007-2022. The project is led by Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania — Director Suzanne Staggs at Princeton, Deputy Director Mark Devlin at Penn — with 160 collaborators at 47 institutions. Credit: Mark Devlin, Deputy Director of the Atacama Cosmology Telescope and the Reese Flower Professor of Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania

“It’s a bit like silhouetting, but instead of just having black in the silhouette, you have texture and lumps of dark matter, as if the light were streaming through a fabric curtain that had lots of knots and bumps in it,” said Suzanne Staggs, director of ACT and Henry DeWolf Smyth Professor of Physics at Princeton University. “The famous blue and yellow CMB image [from 2003] To migawka tego, jak wyglądał wszechświat w jednej epoce, około 13 miliardów lat temu, a teraz daje nam to informacje o wszystkich epokach, które minęły od tego czasu”.

„To ekscytujące móc zajrzeć w to, co niewidzialne i odkryć rusztowanie z ciemnej materii, które podtrzymuje nasze widzialne galaktyki gwiaździste” – powiedział ACT Joe Dunkley, profesor fizyki i nauk astrofizycznych, który prowadzi analizę. „Na tym nowym obrazie możemy zobaczyć z pierwszej ręki niewidzialną kosmiczną sieć ciemnej materii, która otacza i łączy galaktyki”.

„Zwykle astronomowie mogą mierzyć tylko światło, więc widzimy, jak galaktyki są rozmieszczone we wszechświecie. Te obserwacje ujawniają rozkład masy, więc przede wszystkim pokazują, jak ciemna materia jest rozłożona w naszym wszechświecie” – mówi David Spergel, profesor astronomii na Uniwersytecie Princeton, Charles A. .

Badania prowadzone przez Atacama Cosmology Telescope zakończyły się przełomową nową mapą ciemnej materii obejmującą jedną czwartą całego nieba i sięgającą w głąb wszechświata. Wyniki dostarczają dalszego wsparcia dla ogólnej teorii względności Einsteina, która od ponad wieku stanowi podstawę Modelu Standardowego kosmologii, i oferują nowe sposoby demistyfikacji ciemnej materii. Źródło: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda, Simons Foundation

„Zmapowaliśmy rozmieszczenie niewidzialnej ciemnej materii na niebie i jest to dokładnie zgodne z przewidywaniami naszych teorii” – powiedział współautor Blake Sherwin, PhD, 2013. Absolwent Princeton University i profesor kosmologii na University of Cambridge, gdzie kieruje liczną grupą badaczy ACT. „To niesamowity dowód na to, że rozumiemy historię formowania się struktury w naszym wszechświecie przez miliardy lat[{” attribute=””>Big Bang to today.’

He added: “Remarkably, 80% of the mass in the universe is invisible. By mapping the dark matter distribution across the sky to the largest distances, our ACT lensing measurements allow us to clearly see this invisible world.”

“When we proposed this experiment in 2003, we had no idea the full extent of information that could be extracted from our telescope,” said Mark Devlin, the Reese Flower Professor of Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania and the deputy director of ACT, who was a Princeton postdoc from 1994-1995. “We owe this to the cleverness of the theorists, the many people who built new instruments to make our telescope more sensitive, and the new analysis techniques our team came up with.” This includes a sophisticated new model of ACT’s instrument noise by Princeton graduate student Zach Atkins.

Research by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope collaboration has culminated in a groundbreaking new map of dark matter distributed across a quarter of the entire sky, reaching deep into the cosmos. Findings provide further support to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which has been the foundation of the standard model of cosmology for more than a century, and offer new methods to demystify dark matter. Credit: Image courtesy of Debra Kellner

Despite making up most of the universe, dark matter has been hard to detect because it doesn’t interact with light or other forms of electromagnetic radiation. As far as we know, dark matter only interacts with gravity.

To track it down, the more than 160 collaborators who have built and gathered data from the National Science Foundation’s Atacama Cosmology Telescope in the high Chilean Andes observed light emanating following the dawn of the universe’s formation, the Big Bang — when the universe was only 380,000 years old. Cosmologists often refer to this diffuse CMB light that fills our entire universe as the “baby picture of the universe.”

The team tracked how the gravitational pull of massive dark matter structures can warp the CMB on its 14-billion-year journey to us, just as antique, lumpy windows bend and distort what we can see through them.

“We’ve made a new mass map using distortions of light left over from the Big Bang,” said Mathew Madhavacheril, a 2016-2018 Princeton postdoc who is the lead author of one of the papers and an assistant professor in physics and astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. “Remarkably, it provides measurements that show that both the ‘lumpiness’ of the universe, and the rate at which it is growing after 14 billion years of evolution, are just what you’d expect from our standard model of cosmology based on Einstein’s theory of gravity.”

Sherwin added, “Our results also provide new insights into an ongoing debate some have called ‘The Crisis in Cosmology.’” This “crisis” stems from recent measurements that use a different background light, one emitted from stars in galaxies rather than the CMB. These have produced results that suggest the dark matter was not lumpy enough under the standard model of cosmology and led to concerns that the model may be broken. However, the ACT team’s latest results precisely assessed that the vast lumps seen in this image are the exact right size.

“While earlier studies pointed to cracks in the standard cosmological model, our findings provide new reassurance that our fundamental theory of the universe holds true,” said Frank Qu, lead author of one of the papers and a Cambridge graduate student as well as a former Princeton visiting researcher.

“The CMB is famous already for its unparalleled measurements of the primordial state of the universe, so these lensing maps, describing its subsequent evolution, are almost an embarrassment of riches,” said Staggs, whose team built the detectors that gathered this data over the past five years. “We now have a second, very primordial map of the universe. Instead of a ‘crisis,’ I think we have an extraordinary opportunity to use these different data sets together. Our map includes all of the dark matter, going back to the Big Bang, and the other maps are looking back about 9 billion years, giving us a layer that is much closer to us. We can compare the two to learn about the growth of structures in the universe. I think is going to turn out to be really interesting. That the two approaches are getting different measurements is fascinating.”

ACT, which operated for 15 years, was decommissioned in September 2022. Nevertheless, more papers presenting results from the final set of observations are expected to be submitted soon, and the Simons Observatory will conduct future observations at the same site, with a new telescope slated to begin operations in 2024. This new instrument will be capable of mapping the sky almost 10 times faster than ACT.

Of the co-authors on the ACT team’s series of papers, 56 are or have been Princeton researchers. More than 20 scientists who were junior researchers on ACT while at Princeton are now faculty or staff scientists themselves. Lyman Page, Princeton’s James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Physics, was the former principal investigator of ACT.

This research will be presented at “Future Science with CMB x LSS,” a conference running from April 10-14 at Yukawa Institute for Theoretical Physics, Kyoto University. The pre-print articles highlighted here will appear on the open-access arXiv.org. They have been submitted to the Astrophysical Journal. This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (AST-0408698, AST-0965625 and AST-1440226 for the ACT project, as well as awards PHY-0355328, PHY-0855887 and PHY-1214379), Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and a Canada Foundation for Innovation award. Team members at the University of Cambridge were supported by the European Research Council.

„Nieuleczalny student. Społeczny mediaholik. Niezależny czytelnik. Myśliciel. Alkoholowy ninja”.

More Stories

Kiedy astronauci wystartują?

Podróż miliardera w kosmos jest „ryzykowna”

Identyczne ślady dinozaurów odkryto na dwóch kontynentach