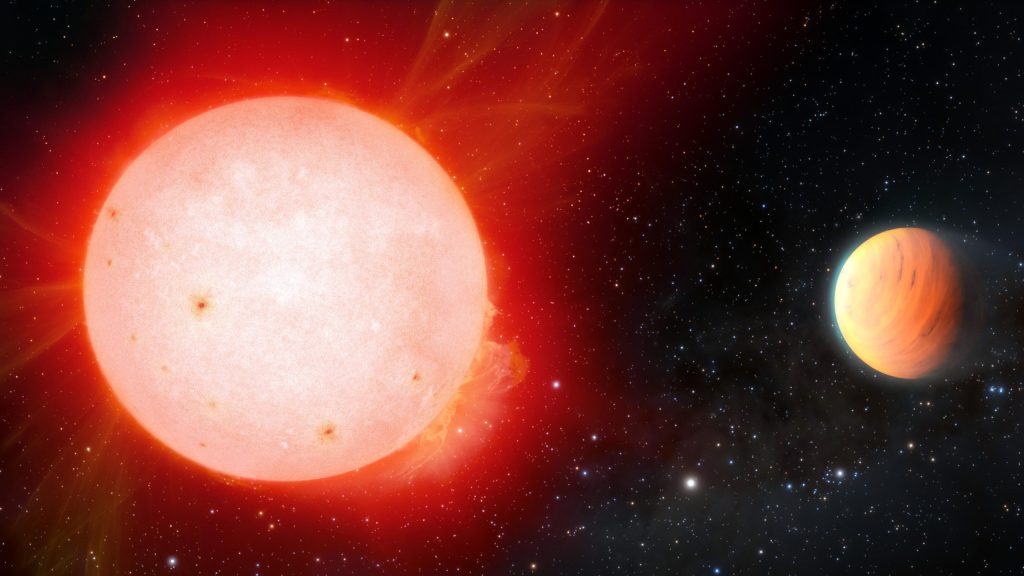

Artystyczne wrażenie bardzo cienkiej gazowej planety olbrzyma krążącej wokół czerwonego karła. Gazowa gigantyczna planeta zewnętrzna [right] Gęstość pianek wykrytych na orbicie wokół chłodnego czerwonego karła [left] przez finansowany przez NASA instrument NEID Radial Velocity Instrument na 3,5-metrowym teleskopie WIYN w Kitt Peak National Observatory, program NSF NOIRLab. Planeta, nazwana TOI-3757 b, jest najcieńszym gazowym gigantem, jaki kiedykolwiek odkryto wokół tego typu gwiazdy. Źródło: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J.da Silva/Spaceengine/M. Zamani

Teleskop Kitt Peak Telescope należący do National Observatory pomaga to ustalić[{” attribute=””>Jupiter-like Planet is the lowest-density gas giant ever detected around a red dwarf.

A gas giant exoplanet with the density of a marshmallow has been detected in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. A suite of astronomical instruments was used to make the observations, including the NASA-funded NEID radial-velocity instrument on the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Named TOI-3757 b, the exoplanet is the fluffiest gas giant planet ever discovered around this type of star.

Using the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, astronomers have observed an unusual Jupiter-like planet in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. Located in the constellation of Auriga the Charioteer around 580 light-years from Earth, this planet, identified as TOI-3757 b, is the lowest-density planet ever detected around a red dwarf star and is estimated to have an average density akin to that of a marshmallow.

Red dwarf stars are the smallest and dimmest members of so-called main-sequence stars — stars that convert hydrogen into helium in their cores at a steady rate. Although they are “cool” compared to stars like our Sun, red dwarf stars can be extremely active and erupt with powerful flares. This can strip orbiting planets of their atmospheres, making this star system a seemingly inhospitable location to form such a gossamer planet.

Shubham Kanodia, badacz z Carnegie Institution for Science’s Earth and Planetary Laboratory i pierwszy autor artykułu opublikowanego w Dziennik astrologicznydo. Do tej pory było to widoczne tylko w małych próbkach przeglądów dopplerowskich, które zwykle znajdowały olbrzymy z dala od czerwonych karłów. Jak dotąd nie mieliśmy wystarczająco dużej próbki planet, aby w solidny sposób znaleźć pobliskie planety gazowe”.

Nadal istnieją niewyjaśnione tajemnice otaczające TOI-3757 b, z których najważniejsza jest to, jak gazowy olbrzym mógł powstać wokół czerwonego karła, zwłaszcza planety o małej gęstości. Jednak zespół Kanodii wierzy, że może znaleźć rozwiązanie tej tajemnicy.

Z Ziemi z Kit Peak National Observatory (KPNO), programu NSF NOIRLab, 3,5-metrowy teleskop Wisconsin-Indiana-Yale-Noirlab (WIYN) wydaje się obserwować Drogę Mleczną wypływającą z horyzontu. Czerwonawy blask atmosferyczny, zjawisko naturalne, również zabarwia horyzont. KPNO znajduje się na Pustyni Sonoran w Arizonie w Tohono O’odham Nation i ten wyraźny widok części płaszczyzny Drogi Mlecznej pokazuje sprzyjające warunki w tym środowisku, potrzebne do oglądania słabych ciał niebieskich. Warunki te, które obejmują niski poziom zanieczyszczenia światłem, ciemniejsze niebo o 20 stopni i suche warunki pogodowe, pozwoliły naukowcom z konsorcjum WIYN kontynuować obserwację galaktyk, mgławic i egzoplanet, a także wielu innych celów astronomicznych przy użyciu WIYN 3.5 -metrowy teleskop i jego siostra, 0,9-metrowy teleskop WIYN. Źródło: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Sparks

Sugerują, że niezwykle niska gęstość TOI-3757 b może być wynikiem dwóch czynników. Pierwsza dotyczy skalistego jądra planety; Uważa się, że gazowe olbrzymy zaczynały jako masywne skaliste jądra o masie około dziesięciokrotnie większej od masy Ziemi, w którym to momencie szybko wciągają duże ilości pobliskiego gazu, tworząc gazowe olbrzymy, które widzimy dzisiaj. TOI-3757b ma mniejszą obfitość ciężkich pierwiastków niż inne karły typu M z gazowymi olbrzymami, co mogło skutkować wolniejszym formowaniem się skalistego jądra, opóźniając początek akumulacji gazu, a tym samym wpływając na ogólną gęstość planety.

Drugim czynnikiem może być orbita planety, którą wstępnie uważa się za nieco eliptyczną. Są chwile, kiedy zbliża się do swojej gwiazdy niż w innych, co powoduje znaczne nadmierne ogrzewanie, które może spowodować pęcznienie atmosfery planety.

Satelita tranzytowy NASA do badań egzoplanet ([{” attribute=””>TESS) initially spotted the planet. Kanodia’s team then made follow-up observations using ground-based instruments, including NEID and NESSI (NN-EXPLORE Exoplanet Stellar Speckle Imager), both housed at the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope; the Habitable-zone Planet Finder (HPF) on the Hobby-Eberly Telescope; and the Red Buttes Observatory (RBO) in Wyoming.

TESS surveyed the crossing of this planet TOI-3757 b in front of its star, which allowed astronomers to calculate the planet’s diameter to be about 150,000 kilometers (100,000 miles) or about just slightly larger than that of Jupiter. The planet finishes one complete orbit around its host star in just 3.5 days, 25 times less than the closest planet in our Solar System — Mercury — which takes about 88 days to do so.

The astronomers then used NEID and HPF to measure the star’s apparent motion along the line of sight, also known as its radial velocity. These measurements provided the planet’s mass, which was calculated to be about one-quarter that of Jupiter, or about 85 times the mass of the Earth. Knowing the size and the mass allowed Kanodia’s team to calculate TOI-3757 b’s average density as being 0.27 grams per cubic centimeter (about 17 grams per cubic feet), which would make it less than half the density of Saturn (the lowest-density planet in the Solar System), about one quarter the density of water (meaning it would float if placed in a giant bathtub filled with water), or in fact, similar in density to a marshmallow.

“Potential future observations of the atmosphere of this planet using NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope could help shed light on its puffy nature,” says Jessica Libby-Roberts, a postdoctoral researcher at Pennsylvania State University and the second author on this paper.

“Finding more such systems with giant planets — which were once theorized to be extremely rare around red dwarfs — is part of our goal to understand how planets form,” says Kanodia.

The discovery highlights the importance of NEID in its ability to confirm some of the candidate exoplanets currently being discovered by NASA’s TESS mission, providing important targets for the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to follow up on and begin characterizing their atmospheres. This will in turn inform astronomers what the planets are made of and how they formed and, for potentially habitable rocky worlds, whether they might be able to support life.

Reference: “TOI-3757 b: A low-density gas giant orbiting a solar-metallicity M dwarf” by Shubham Kanodia, Jessica Libby-Roberts, Caleb I. Cañas, Joe P. Ninan, Suvrath Mahadevan, Gudmundur Stefansson, Andrea S. J. Lin, Sinclaire Jones, Andrew Monson, Brock A. Parker, Henry A. Kobulnicky, Tera N. Swaby, Luke Powers, Corey Beard, Chad F. Bender, Cullen H. Blake, William D. Cochran, Jiayin Dong, Scott A. Diddams, Connor Fredrick, Arvind F. Gupta, Samuel Halverson, Fred Hearty, Sarah E. Logsdon, Andrew J. Metcalf, Michael W. McElwain, Caroline Morley, Jayadev Rajagopal, Lawrence W. Ramsey, Paul Robertson, Arpita Roy, Christian Schwab, Ryan C. Terrien, John Wisniewski and Jason T. Wright, 5 August 2022, The Astronomical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ac7c20

„Nieuleczalny student. Społeczny mediaholik. Niezależny czytelnik. Myśliciel. Alkoholowy ninja”.

More Stories

Kiedy astronauci wystartują?

Podróż miliardera w kosmos jest „ryzykowna”

Identyczne ślady dinozaurów odkryto na dwóch kontynentach